As part of a series of experiential learning projects, I will be preparing and using a variety of historic materials. The objective here is less about perfecting these historic methods (in terms of strict historical accuracy – although accuracy is still important) and more about what we can learn by doing rather than by using the traditional research methods of reading and writing. This feeds into the pedagogical work we are undertaking at the moment in relation to experiential learning and thinking about how physical engagement aids cognitive engagement.

Iron gall ink is produced by the reaction of tannic acid extracted from tree galls, a type of growth on trees (especially oak), with ferrous sulphate (FeSO4).

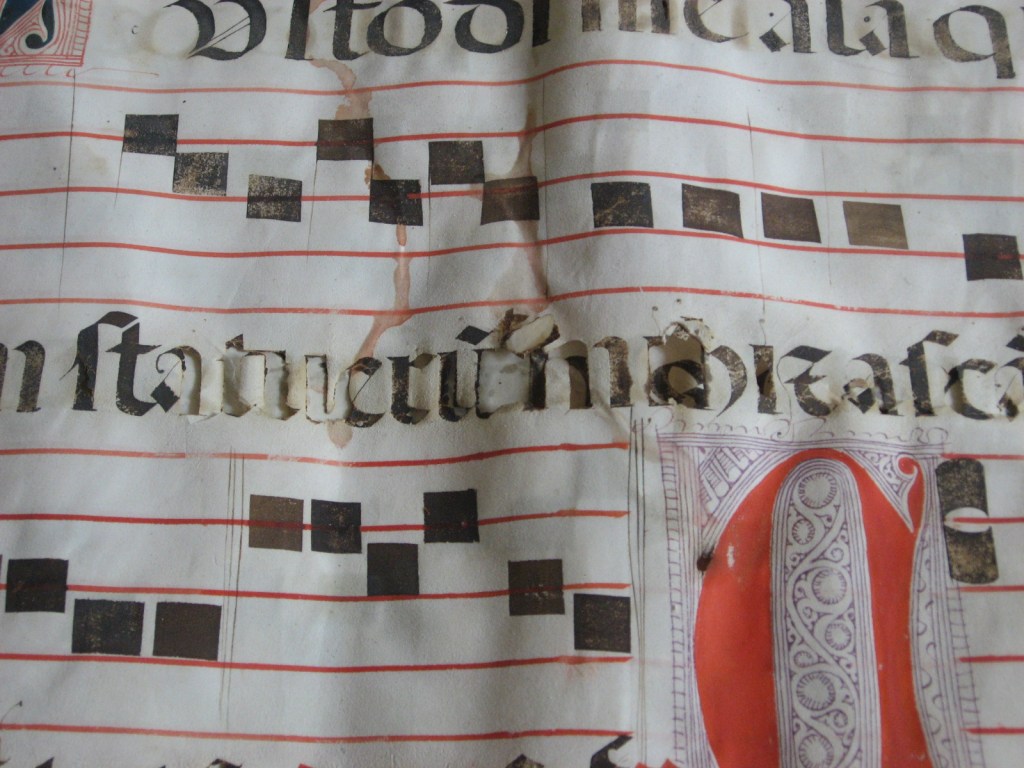

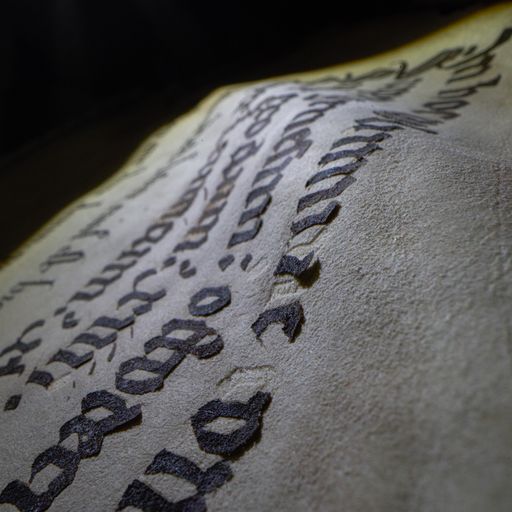

Iron gall ink has been commonly used in the production of European manuscripts from the 9th century until the 20th century. One of the earliest recipes for oak gall ink comes from Pliny the Elder, however, a lot of historical manuscripts written with this ink have suffered terrible damage caused by the acid eating through the support. Poor quality ink fades, and can cause the paper around the ink to darken and become brittle. This can lead to the creation of fragments or complete loss of the stability of the support. Occasionally also, the ink does not sufficiently adhere to its support and eventually the letters begin lifting off [see: Katerina Powell (2010) Analysis and consolidation of lifting ink in a

twelfth‐century manuscript, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 33:1, 13-27 also https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=24454]

Ingredients:

Various recipes for iron gall ink survive from the medieval and late-medieval periods, here I used the following:

– 7 galls (7g)

– water (100ml)

– ferrous sulphate (1 tsp)

– gum arabic (1 tsp)

- Oak Gall: A growth caused by insects, usually a wasp or fly, which lay eggs into young tissue in the tree. The larvae grow up in the gall, which has a higher quantity of gallotannic acid than the rest of the tree.

- Water (H2O)

- Ferrous sulphate (FeSO4): A metallic salt that forms blue-green crystals. In ancient times, people used naturally occurring melanterite (FeSO4・7H2O).

- Gum Arabic: Resin extracted from the acacia tree, a translucent amber colour. It works in the ink both as a binder and to modify its flow. It allows for better surface tension of the ink on the nib and makes it easier to write more with each dip into the ink.

Method of making iron gall ink

- Break the oak galls into pieces using a pestle and mortar.

The insides of the galls tend to reflect their outer colours: black, yellow or reddish brown.

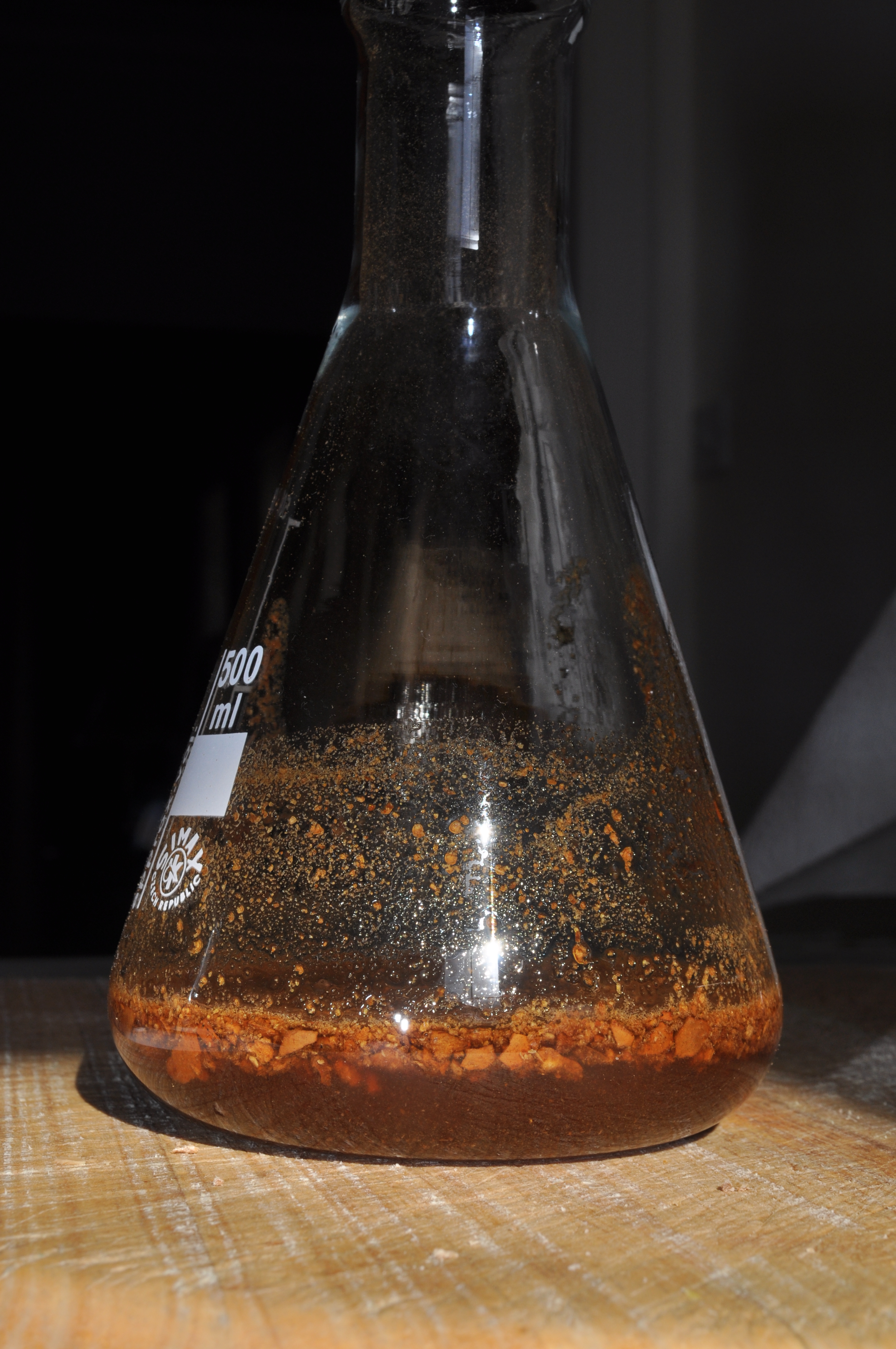

- Add the water to the ground galls.

Gallotannnic acid is extracted by heating or just soaking for a few days. Gallotannin is hydrolysed to gallic acid and glucose.

The liquid turned dark brown in about 3 minutes. Note that conical flasks are heatproof and I therefore applied some heat to speed up the process, but this could equally be done by using a small saucepan.

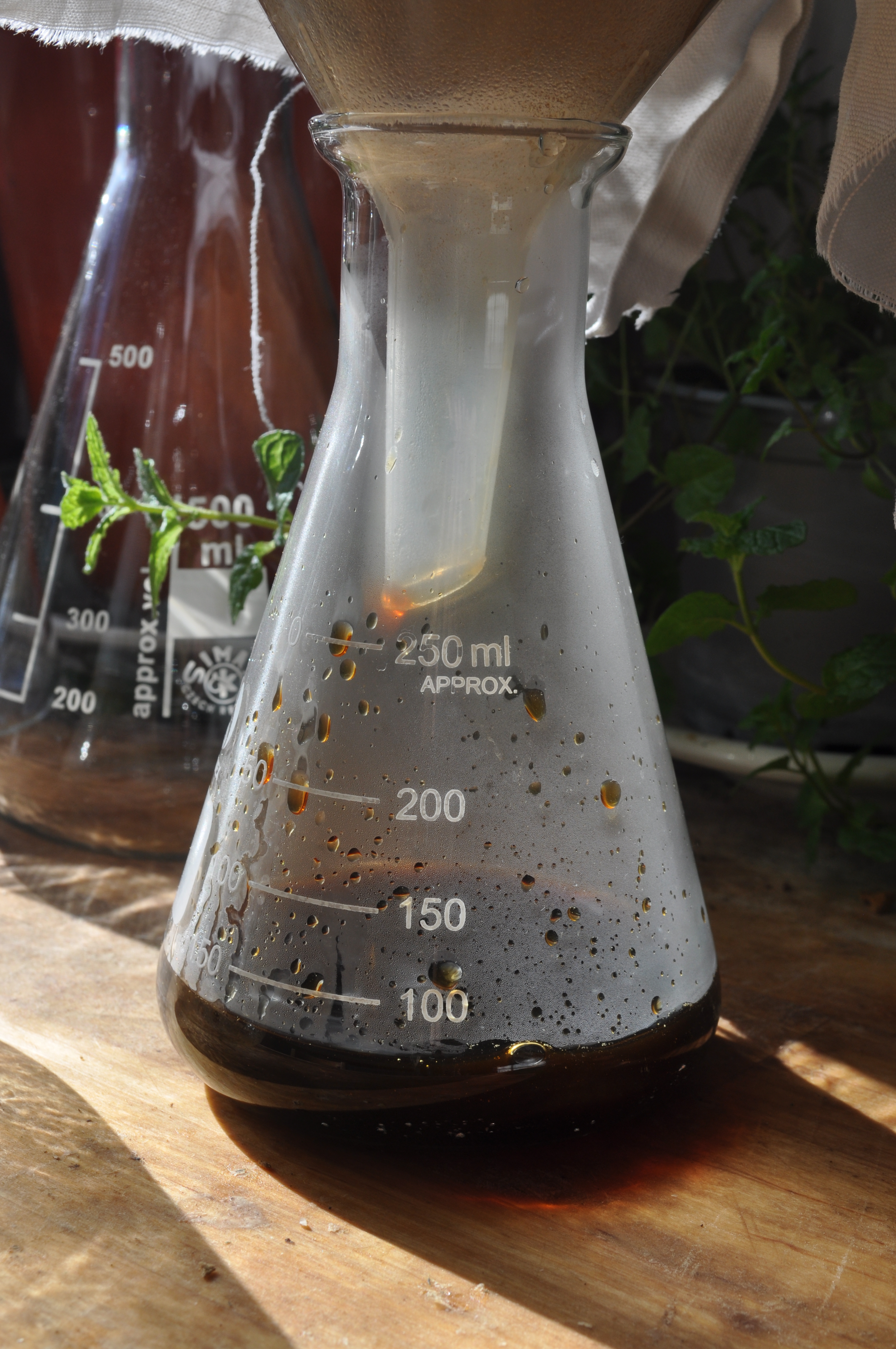

- Next filter the gall and water mixture.

The ink was filtered once using a funnel and piece of thick cotton.

- Add the ferrous sulphate

After adding ferrous sulphate to the solution, the colour turned from brown to black immediately. This is because gallic acid reacts with ferrous cations; together they make ferrous gallate, which is black in colour.

gallic acid + ferrous cation -> ferrous gallate

- Add the gum arabic. Gum arabic is a gum that is exuded from certain trees, such as the Acacia senegal tree.

Crushed gum arabic is put into the solution. This is then stirred until it dissolved, at which point the ink was more or less completed.

However, be careful that the gum arabic doesn’t just sink and stick to the base of the flask.

When the ink was applied, it was initially a translucent grayish brown, over a few seconds, the colour gradually turned deep black.

This is the reaction of ferrous gallate and oxygen from the air. The black of iron gall ink comes from ferric pyrogallate (the Fe2+ is oxidized to Fe3+).

ferrous gallate + oxygen -> ferric pyrogallate + H2O

And there we have it: one method for oak gall ink.

I have added below another that can be found in the National Archives:

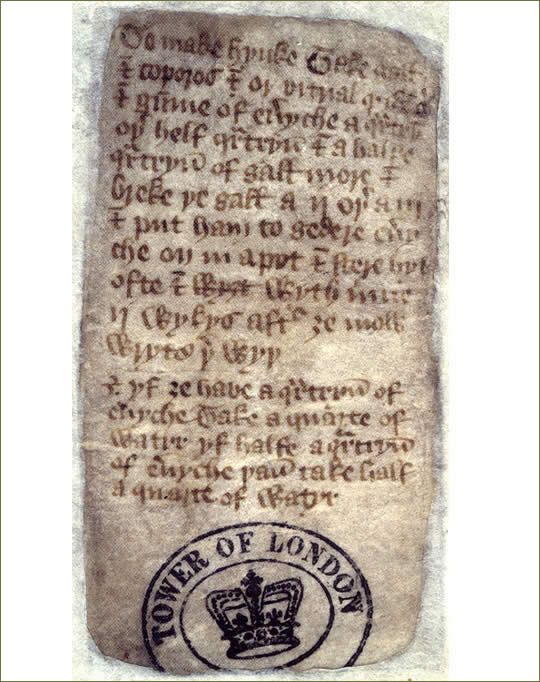

To make hynke. Take gall

& coporos & or vitrial quartryn

& gumme of eueryche a quartryn

oþer helf quartryn & a halfe

quartryn of gall more &

breke þe gall a ij oþer a iij

& put ham togedere euery-

che one in a pot & stere hyt

ofte & wyƷt wythinne

ij wykys after Ʒe mow

wryte þer wyþ.

& yf Ʒe have a quartryn of

eueryche take a quarte of

watyr yf halfe a quartryn

of eueryche þan take half

a quartre of watyr.

[transcription by prof. Sarah Peverley]

The recipe instructs that the same four substances as used above should be mixed together in equal measure: oak galls, copperas (aka iron sulfate, ferrous sulfate or iron vitriol), gum arabic, and water. The mixture should be stirred often over a two week period, after which time it is ready to use.

The National Archives of the UK, C 47/34/1/3.

Sarah Gilbert, A Curious Cure for a Cambridge Book – Part One, https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=24454

Katerina Powell (2010) Analysis and consolidation of lifting ink in a

twelfth‐century manuscript, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 33:1, 13-27.

An extensive list of sources can be found here:

Leave a comment