Experiential learning is a philosophy of learning built around the idea of learning by doing and then reflecting on the experience. This current project aims to do just that. Learning about manuscript illumination as a process by trying to recreate the objects of my studies using (as far a possible) historically appropriate materials, methods and techniques.

The aims of the project are threefold:

- to learn about process, skill, materials and technique by using hands-on research.

- to consider how such research might further pedagogy in manuscript studies – testing the feasibility of such activities as teaching methods.

- to consider how slow-engagement with materials allows for the time necessary to read and understand images in a more meaningful way.

This post is really just a place for me to consider my initial thoughts and log the ideas that I aim to develop further in an academic article in due course.

Materials and techniques:

In undertaking this project, I used historically accurate materials as far as possible. In relation to this I am indebted to the work of Patricia lovett whose many publications on calligraphy, illumination, materials and techniques have been invaluable.

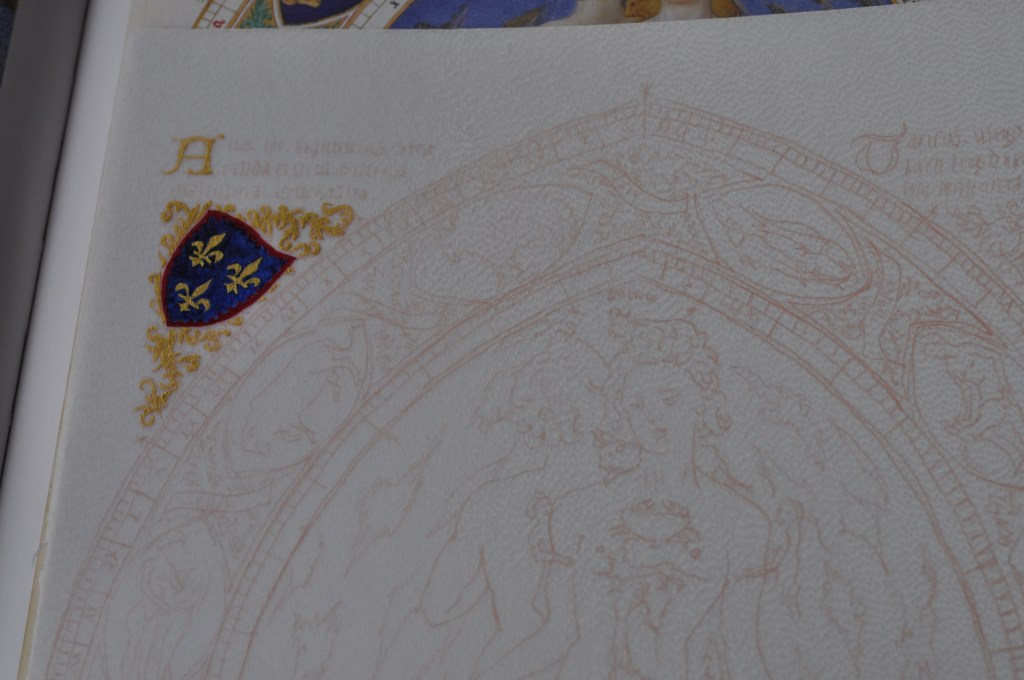

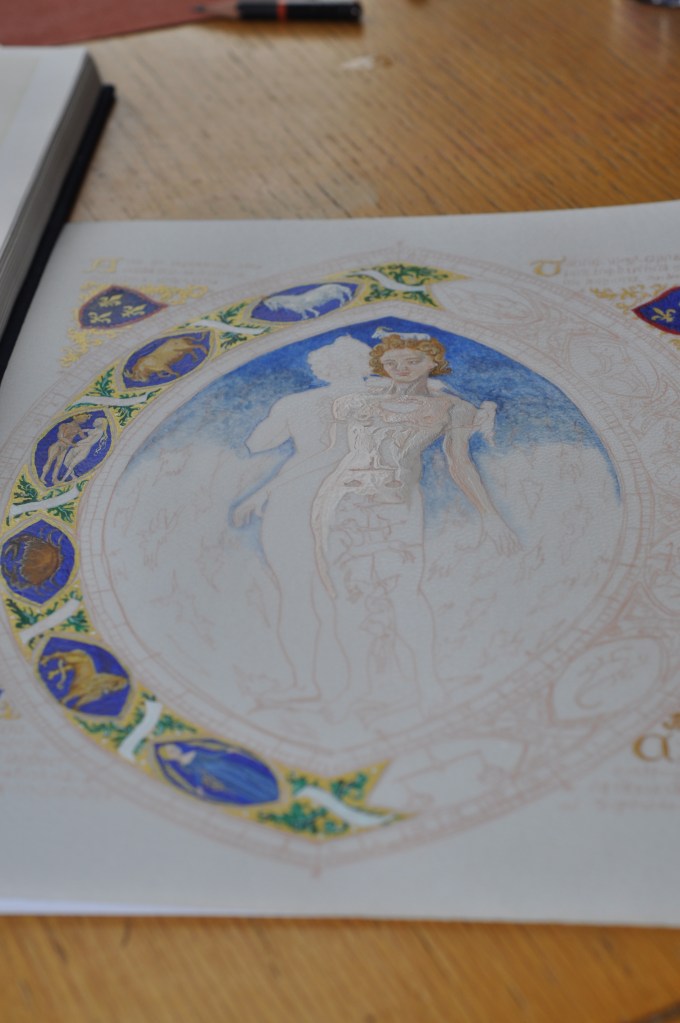

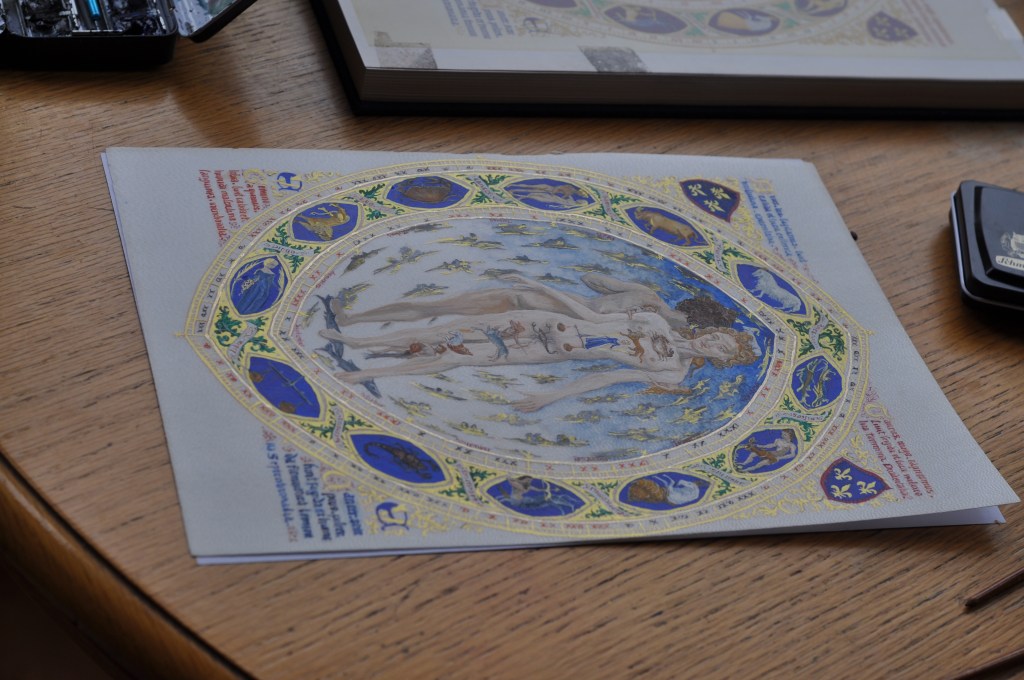

It was important in this project to follow the scale and proportions used by the Limbourg brothers and therefore the outline needed to be transferred from a to-scale tracing of the zodiac man. For this I needed to make a form of carbon paper using Armenian bole powder.

There is a great deal of individual subjectivity in the process of drawing. People aren’t predictable, and everyone has a slightly different frame of reference from which they ‘see’ their subject. Therefore adhering to the Limbourgs’ exact proportions was important for this exercise.

This is moreover a historically accurate method employed in manuscript illumination. Images were at times transferred in this manner. For example, Cennini notes how to make a form of tracing paper from fine kid parchment & linseed oil.

The outline is then reinforced with a very fine brush and lead red.

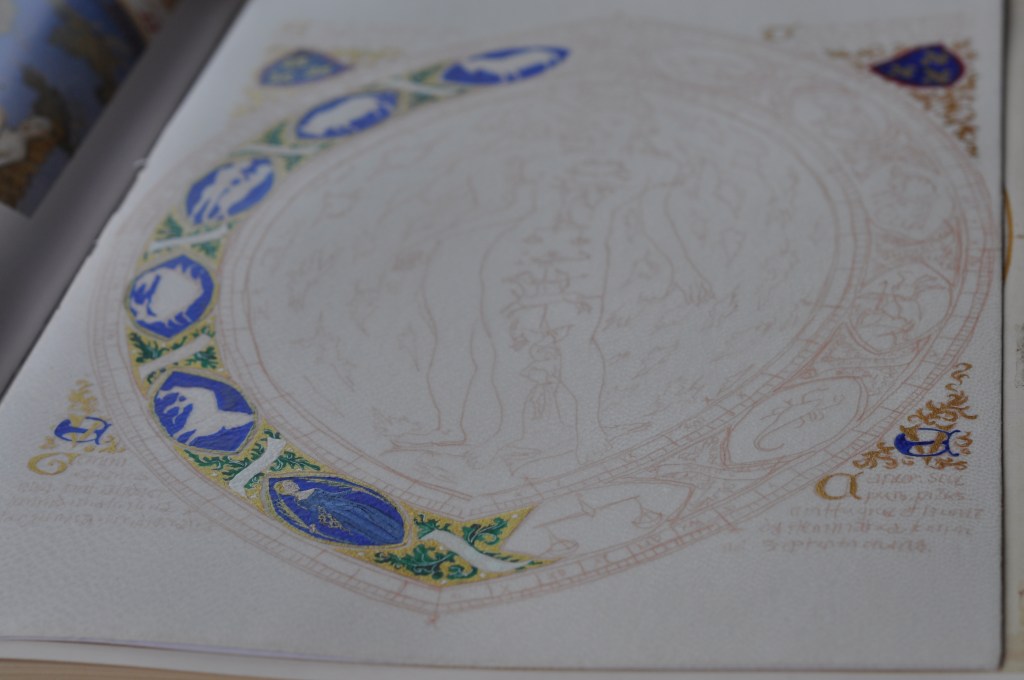

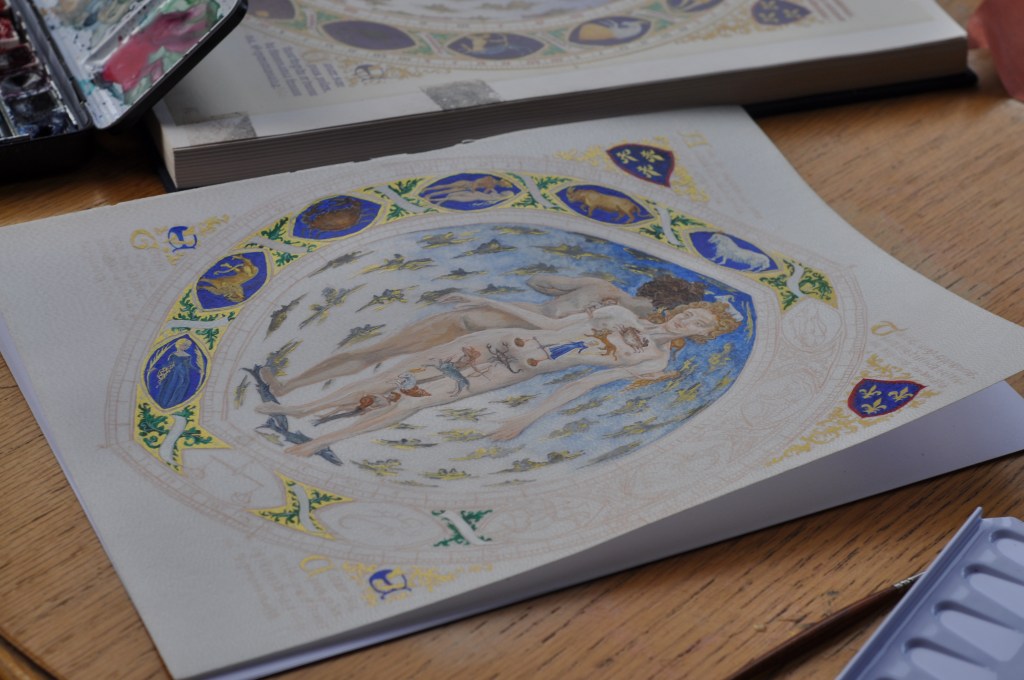

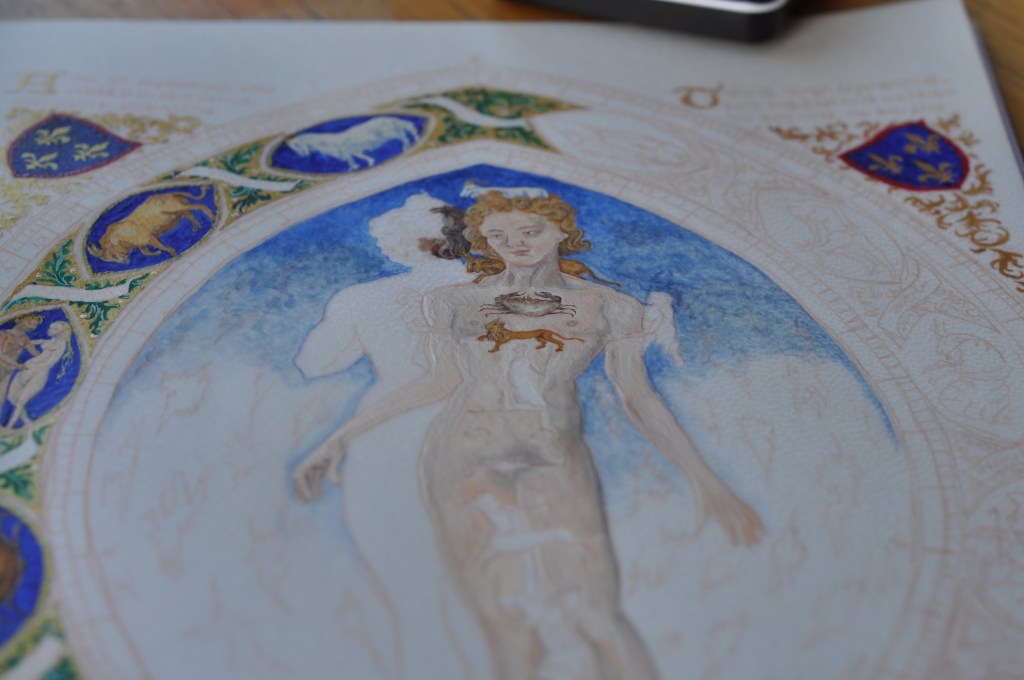

As I have tried to show here, it is the use of metals that really make illuminations so unusual and vivid.

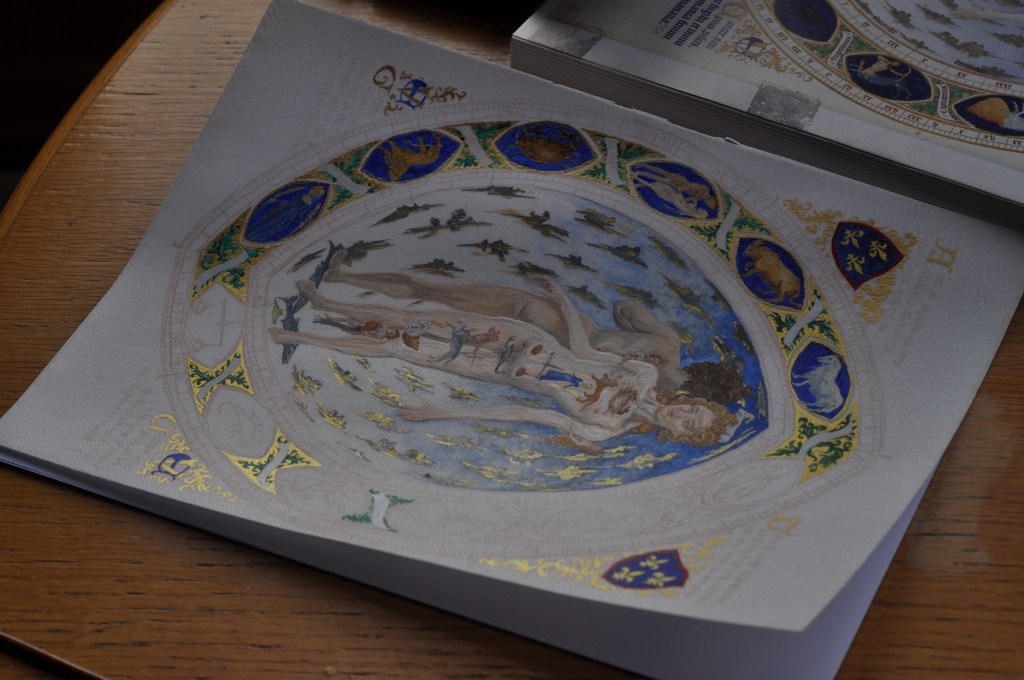

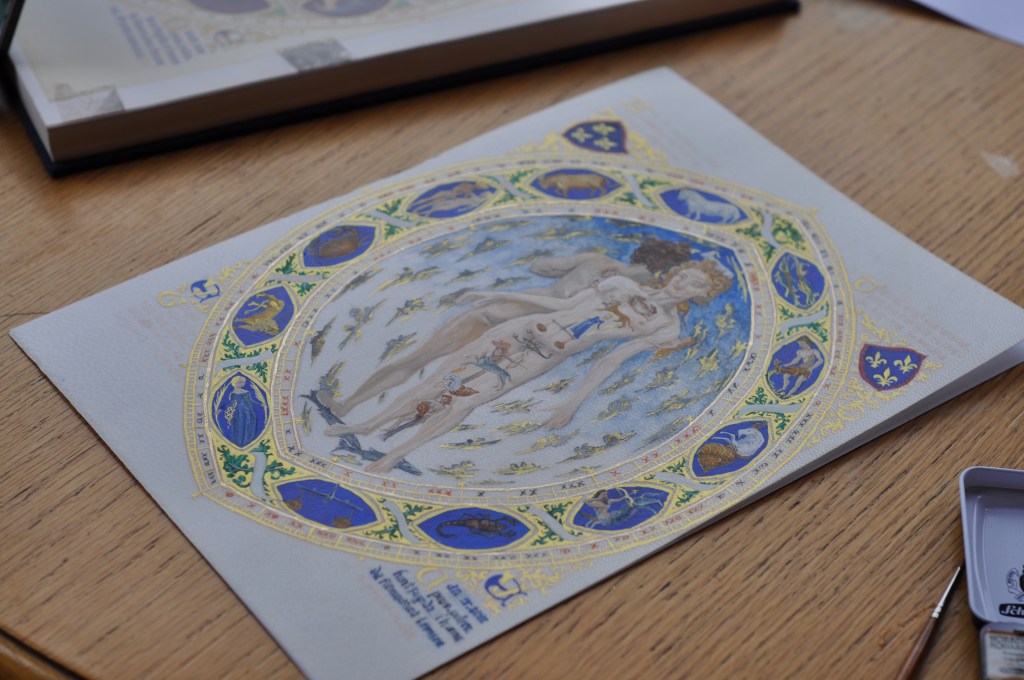

The light reflected by metal pigments, or leaf, in illuminations appears to radiate from the folio when it is turned. In this example it was not gold leaf that I used, but rather a mosaic gold which has a rather different effect – the significance of which I will come back to….

The process was slow. Even my finest brushes were at times too clumsy and it used an exhausting amount of concentration to achieve even the smallest section. I discovered that there was a necessity to working from left to right on a sheet of parchment this size, since you really didn’t want your resting hand to smudge wet pigment…

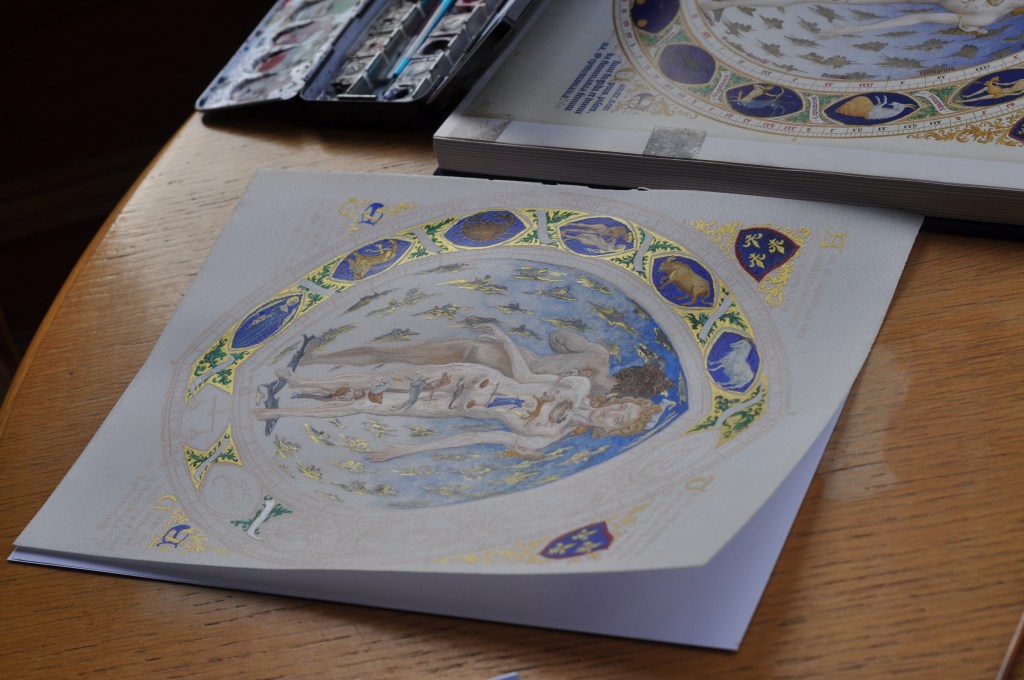

The process of painting on parchment is furthermore peculiar and unlike any painting I had done previously on paper, canvas or panel. It is strangely satisfying. The pigment can be manipulated on top of the parchment with no absorption or spread. Errors can be fairly easily corrected, except when the pigment gets trapped in the hair follicles. There is a greater possibility for building up layers of colours and manipulating the way the pigment sits on top of the skin. It is much more of a 3-dimensional image building process than I had previously considered…

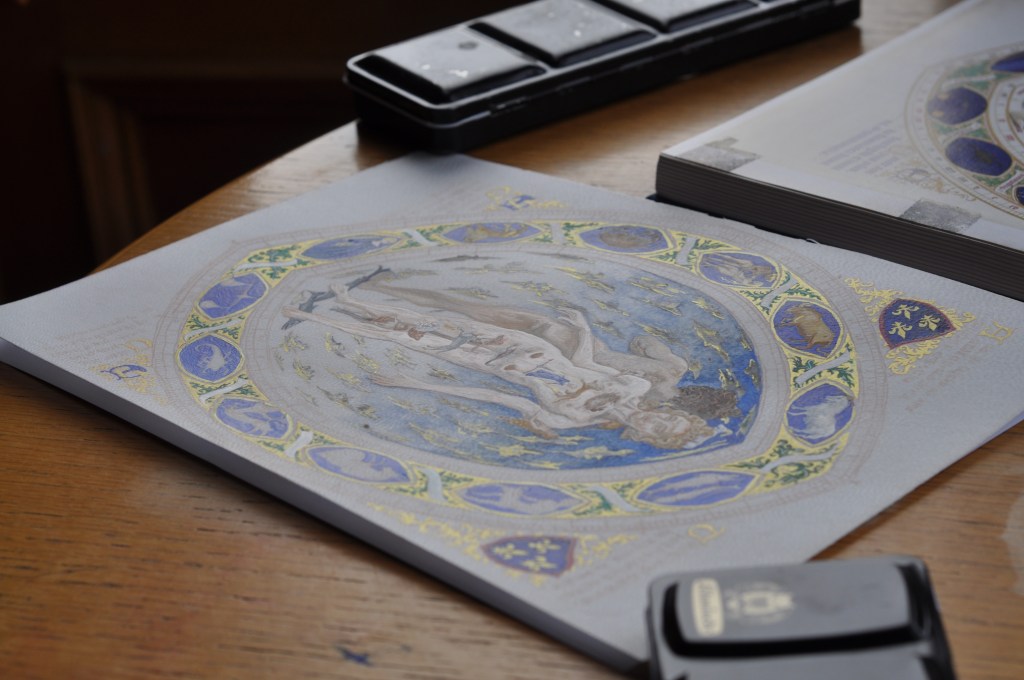

Yet the drying time seemed relatively fast. This did however potentially impact the way the parchment behaved and the series of three images above go some way to show how that parchment moved over time – curling and bending like a fortune fish…

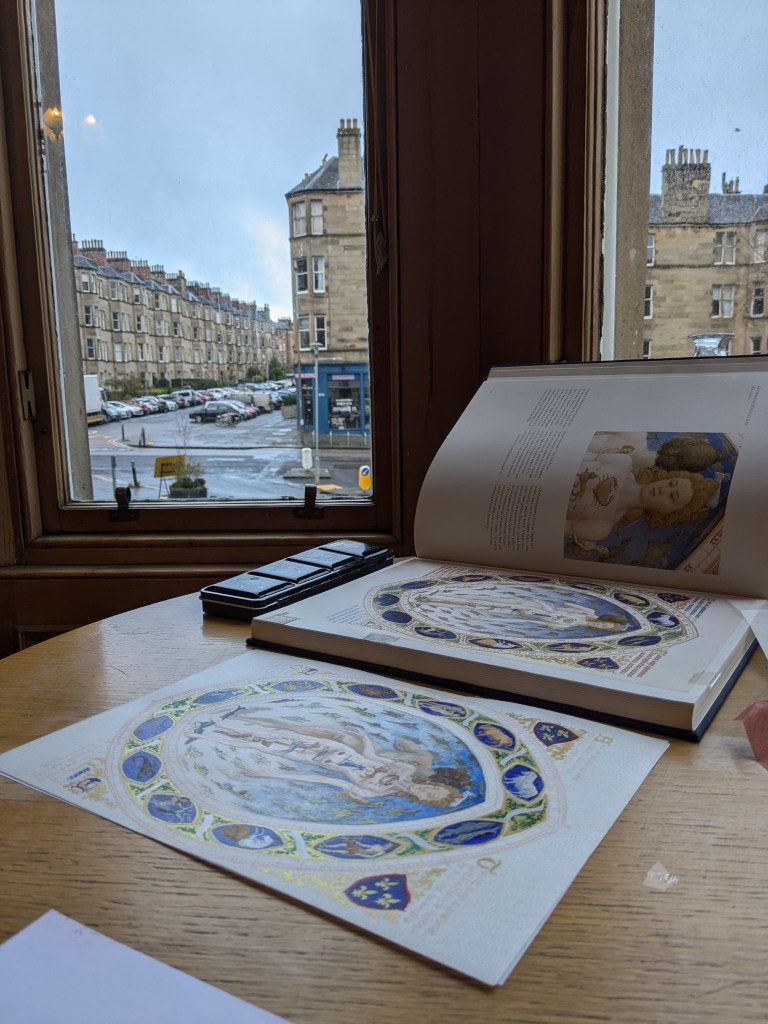

One other key factor was light. working in artificial light was not easy and therefore work times were limited to those periods with good natural light. I positioned myself by a window but had to work around my university schedule, mainly confining my illuminating time to weekends.

Academic findings:

Many of the images that I have taken are at an angle. This is in an attempt to convey the optical effect of working with these materials – where, with each bodily movement, the light reflects off the metal pigments in a slightly different manner. Making it a constantly fluctuating optical experience.

This process makes you very aware of the materiality of the image as an object. The metal is much more prevalent than typical reproductions might lead you to believe and the image becomes (in this instance) an intricate machine or metal mechanical device for calculating time.

When we remember that two of the Limbourg brothers trained as goldsmiths, this has potentially an even greater significance.

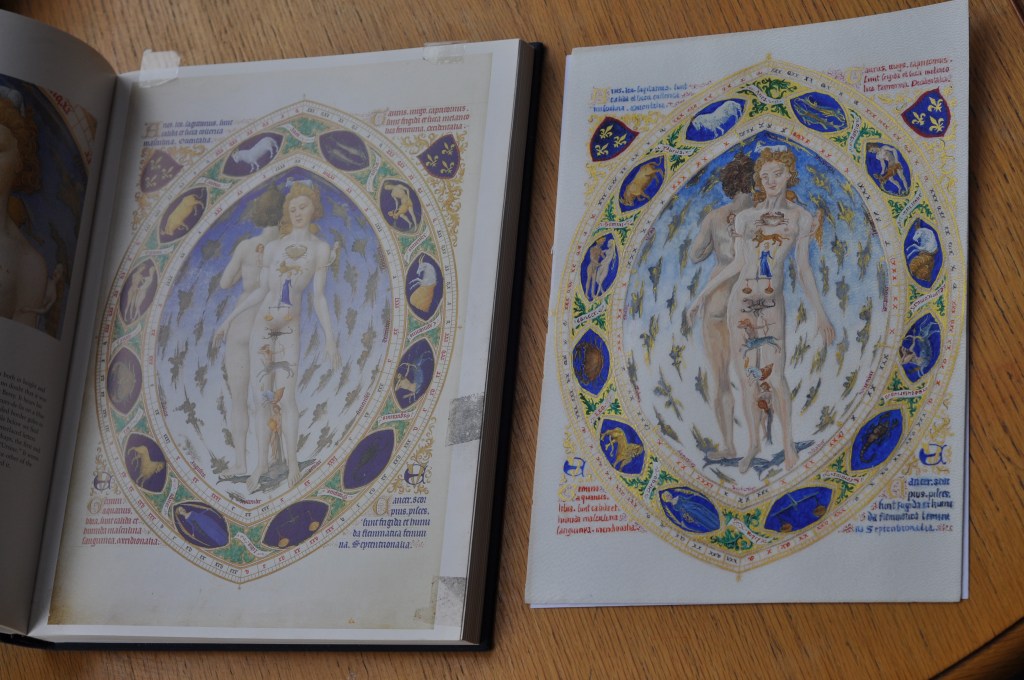

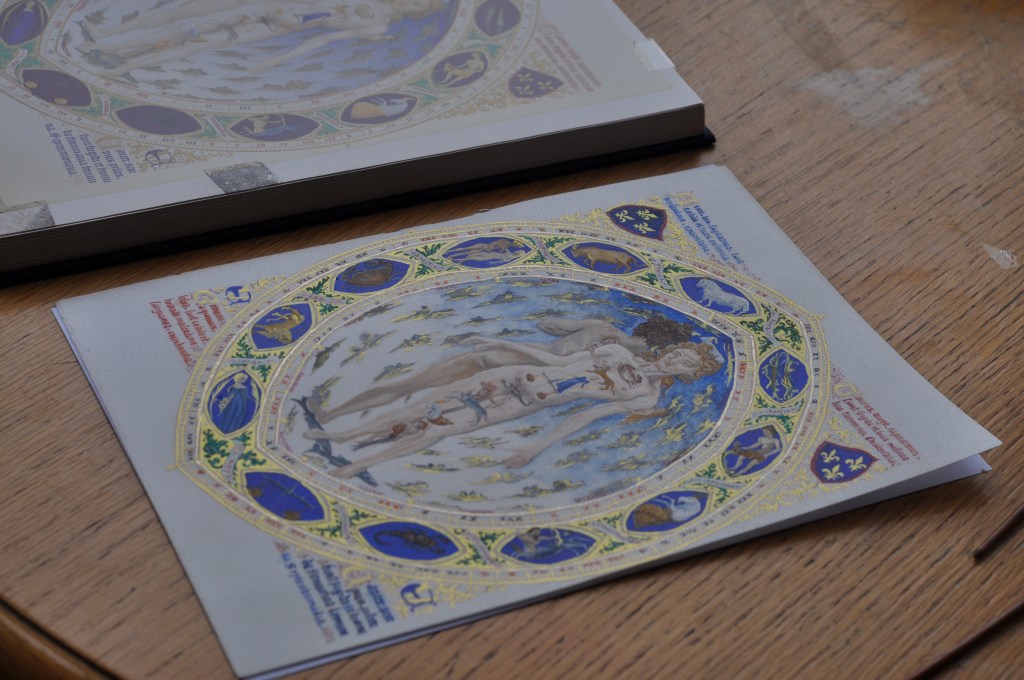

[The Limbourg brothers, Measuring the heavens, BnF MS fr 166].

The macrocosm is what happens in the universe (e.g. the movement of the planets). While the microcosm is what happens inside man. These two spheres were, in medieval times, thought to be closely linked. The key idea behind the zodiac man iconography was, therefore, to make visible an iconographic representation of this celestial correlation. The movement of the planets were thought to effect the various parts of the body and the image that the Limbourgs’ composed is a useful diagrammatic rendering of these supposed influences. There is no escaping the macro-/micro- cosmic idea in this image since the central figures are literally enveloped in a swirling, fiery atmosphere of light, and air, and clouds.

By working closely with the Limbourgs version of this iconography I was able to think carefully about some of its more unusual features. The twinning figural aspect, gender, and deliberate complexity being some of the key areas that become inescapable when you engage with the image on a close level. By reproducing this macro-/micro-cosm idea within a computational machine, set-up with a complex level of timekeeping data – the image goes far beyond the standard iconography. This is an area, I am working on in relation to a publication on this project, but for now, I will end with one of my key findings: making helps you to see more clearly and by engaging physically with the act of creating such an image, new knowledge is, I would argue, always revealed.

Leave a comment